Plastic pollution has become one of the most pressing environmental crises of our time. Every year, the world generates over 400 million tons of plastic waste, with over 14 million tons ending up in the ocean. Most of this waste consists of non-biodegradable plastics, which persist for centuries in landfills, waterways, and ecosystems.

These plastics are derived from fossil fuels like crude oil and natural gas, contributing to both environmental degradation and carbon emissions.

As concerns over plastic pollution grow, many see biodegradable plastics as a promising alternative.

However, the term is often misunderstood.

Unlike conventional plastics, biodegradable plastics are designed to decompose naturally with the help of specific microorganisms, breaking down into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass under the right conditions.

From a circular economy perspective, biodegradable polymers offer a way to reduce plastic waste while promoting reuse and compostability. If properly managed, they could help mitigate the long-term damage caused by petroleum-based plastics, clearing the way for a more sustainable future.

What Is Biodegradable Plastic?

Biodegradable plastic is a type of plastic material designed to decompose naturally through the action of microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi.

Unlike conventional plastics, which can persist for centuries, biodegradable plastics break down into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass under specific environmental conditions.

However, not all biodegradable plastics degrade at the same rate.

Some are readily biodegradable, meaning they break down quickly under common conditions, while others are inherently biodegradable, requiring specialized environments to decompose efficiently.

The biodegradability of plastic depends largely on its polymer structure and chemical properties. For instance, polylactic acid (PLA), derived from plant waste, degrades under higher temperatures found in industrial composting facilities, whereas polybutylene adipate terephthalate (PBAT) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) are engineered to degrade more efficiently in varied conditions.

More on the classification later.

Environmental factors such as oxygen availability, temperature, and moisture play a crucial role in biodegradation. In aerobic environments (e.g., industrial composting), plastics break down faster, whereas in anaerobic conditions (e.g., landfills), the process is much slower, sometimes leading to methane emissions.

Marine environments pose another challenge, as many biodegradable plastics require specific microorganisms to facilitate degradation—organisms that may not always be present in ocean ecosystems.

Are Compostable and Biodegradable Plastics the Same?

No, compostable plastics and biodegradable plastics are not the same—although, some interchange the terms very casually. Biodegradable plastic refers to any plastic that eventually breaks down with the help of microorganisms, but the timeframe and conditions vary widely.

Some may take decades, while others break down only under specific conditions.

Compostable plastics, on the other hand, must degrade within a set timeframe in industrial composting facilities, leaving no toxic residue behind. They require higher temperatures and aerobic conditions to convert into carbon dioxide, water, and nutrient-rich compost.

While all compostable plastics are biodegradable, not all biodegradable plastics are compostable.

Like I said earlier, PLA-based plastic bags require industrial composting to fully degrade, whereas oxo-degradable plastics merely fragment, contributing to plastic pollution rather than fully decomposing.

Biodegradable Plastic Classification

Biodegradable plastics fall into several categories based on their chemical composition, feedstock sources, and end-of-life pathways. While some are derived from renewable resources, others still rely on fossil fuels but are designed to break down under specific conditions.

1. Bioplastics

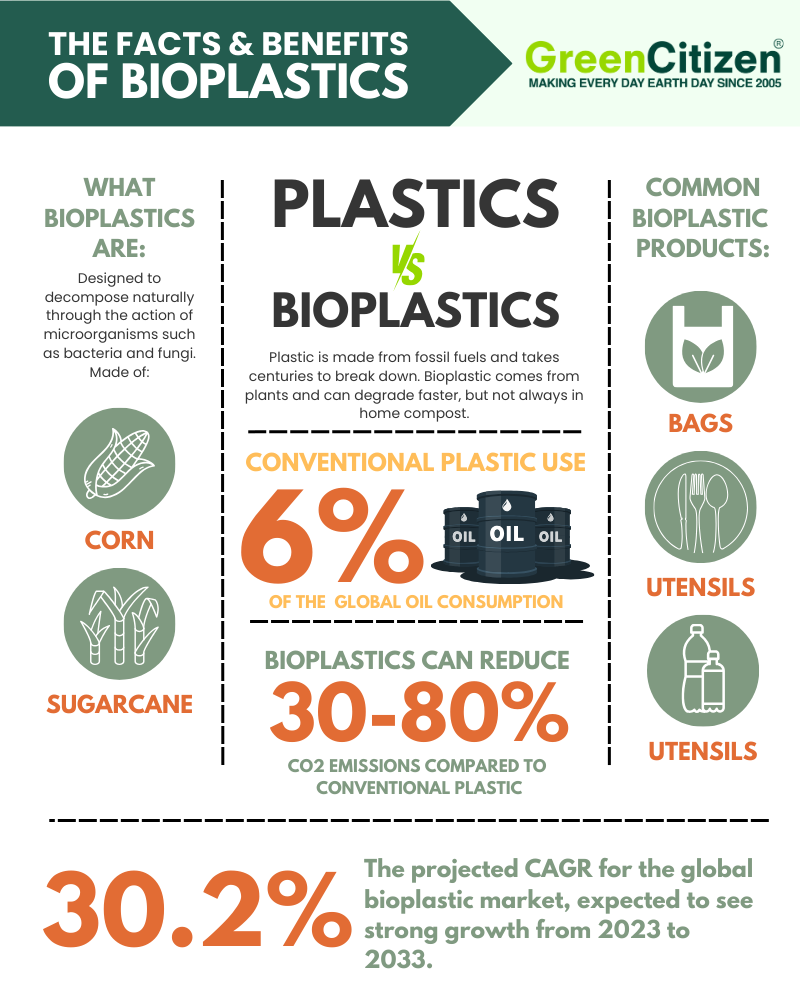

Bioplastics are plastics partly or entirely derived from renewable resources like plant waste, cellulose, corn, and sugarcane. Unlike traditional petroleum-based plastics, bioplastics aim to reduce reliance on fossil fuels while offering similar functionality.

Common types include:

- Polylactic Acid (PLA): Derived from corn starch or sugarcane, widely used in food packaging and plastic bags. It decomposes naturally under higher temperatures in industrial composting facilities.

- Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA): Produced by specific microorganisms, making it one of the most readily biodegradable bioplastics, even in marine environments.

- Bio-based PET: A version of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) made from renewable resources like sugarcane, but it behaves similarly to conventional plastics and does not readily biodegrade.

2. Bio-Based Plastic

Bio-based plastics emphasize renewable materials rather than end-of-life biodegradability. Some still persist in the environment like traditional plastics.

Examples include:

- Bio-based PE (polyethylene): Derived from sugarcane ethanol but chemically identical to low-density polyethylene (LDPE). It does not biodegrade but reduces dependence on crude oil.

- Bio-based PET: While partially made from plant-based materials, it does not degrade like PLA or PHA.

3. Petroleum-Based Biodegradable Plastic

While most biodegradable plastics aim to replace fossil fuel-derived plastics, some still originate from crude oil but are designed to degrade faster.

Examples include:

- PBAT (Polybutylene Adipate Terephthalate): A petroleum-based plastic that decomposes naturally in industrial composting.

- Certain biodegradable polyesters: Modified to break down under aerobic conditions but still dependent on fossil fuels.

4. Oxo-Degradable Plastic

Oxo-degradable plastics contain additives that help them fragment into smaller pieces when exposed to oxygen, heat, or sunlight. However, they do not fully biodegrade and often leave behind microplastic pollution.

Key concerns:

- Misleading claims: Marketed as "biodegradable" but do not meet true biodegradability standards.

- Regulatory bans: Some regions have restricted oxo-degradable plastic due to concerns about environmental harm.

How Does the Biodegradation Process Work?

Biological Mechanism

Biodegradation occurs when microorganisms like bacteria, fungi, and algae break down plastic polymers into simpler molecules. This process happens through enzymatic activity, where microbes secrete enzymes that cleave long polymer chains into smaller monomers.

In the case of polylactic acid (PLA), enzymes break it down into lactic acid, which can then be further consumed by microbes.

The final byproducts of this process depend on environmental conditions. Under aerobic conditions, such as in industrial composting, plastics break down into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass.

However, in anaerobic environments like landfills, the degradation process is slower and can produce methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Physical and Chemical Conditions

Several factors influence how quickly biodegradable plastics break down. Moisture and oxygen levels, temperature, and pH all play a crucial role. Industrial composting facilities, for example, maintain temperatures above 50°C to accelerate decomposition.

The chemical composition of a plastic also impacts its degradation speed. Plastics with ester bonds, like PLA, degrade faster under microbial activity, while others require specific conditions. Mechanical pre-processing, such as shredding or chopping, increases surface area exposure, allowing microbes to break down the material more efficiently.

How Long Does it Take for Biodegradable Plastic to Degrade?

The degradation time for biodegradable plastics varies widely depending on the environment. In industrial composting, they decompose within three to six months.

Whereas in home composting, they may take years due to lower temperatures and microbial activity.

Some biodegradable plastics, if improperly disposed of in landfills or marine environments, may persist for decades, whereas non-biodegradable plastics can remain intact for hundreds of years.

The Origins and Commercialization of Biodegradable Plastic

The concept of biodegradable plastics dates back to the early 20th century when scientists began experimenting with natural polymers.

One of the earliest biodegradable films was cellophane, made from cellulose, which laid the groundwork for future research into biodegradable alternatives. By the mid-20th century, researchers explored microbial processes to create biodegradable polymers, setting the stage for modern innovations.

In the 1990s, Cargill Dow LLC (now NatureWorks) became a key player in the commercialization of biodegradable plastics, introducing polylactic acid (PLA) under the brand Ingeo. Other innovators focused on polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), a biodegradable polymer produced by bacteria fermenting plant-based feedstocks.

These developments marked the beginning of large-scale biodegradable plastic production.

As environmental concerns over plastic waste grew, biodegradable plastics gained traction, particularly in food packaging, plastic bags, and single-use products.

Increased consumer demand and legislation restricting petroleum-based plastics further accelerated their adoption. Many governments introduced bans on conventional plastic items, pushing industries toward biodegradable and compostable alternatives.

Today, biodegradable plastics continue to evolve, driven by innovation and regulatory support.

Common Commercial Biodegradable Plastic Examples

Polylactic Acid (PLA)

PLA is one of the most widely used biodegradable plastics, derived from lactic acid produced by fermenting corn starch or sugar beet. It is commonly found in food packaging, disposable cups, and plastic films.

Common commercial products made with PLA:

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA)

PHA is a naturally occurring biodegradable plastic biosynthesized by bacteria using renewable feedstocks like plant waste and biomass.

It is used in medical applications, such as sutures and drug delivery systems, as well as biodegradable packaging.

PHA stands out for its ability to degrade efficiently in marine and soil environments, making it a promising alternative to conventional plastics that persist in nature.

Common commercial products made with PHA:

Polybutylene Adipate Terephthalate (PBAT)

PBAT is a petroleum-based polymer designed to be biodegradable, often blended with PLA to improve flexibility and durability. It is widely used in certified compostable plastic bags and films.

Common commercial products made with PBAT:

- BioBag compostable waste bags

- Futamura NatureFlex films

- Novamont Mater-Bi biodegradable bags

Starch-Based Plastics

Starch-based plastics are blends of natural starches (from corn, potatoes, or cassava) with other biodegradable polymers.

They are commonly found in loose-fill packing peanuts, which dissolve in water and decompose naturally. These plastics offer an eco-friendly alternative to expanded polystyrene (EPS) but may lack the strength of synthetic biodegradable plastics.

Common commercial products made with starch-based plastics:

Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA)

PVA is a water-soluble synthetic polymer that readily biodegrades under the right conditions.

It is used in detergent pouches, agrochemical packaging, and dissolvable medical films. Its ability to dissolve in water makes it an effective material for applications requiring controlled breakdown, but it requires specific microbial conditions to ensure complete degradation.

Common commercial products made with PVA:

How to Identify Biodegradable Plastics: Standards, Labels, and Certifications

With the rise of eco-friendly products, misleading claims about biodegradability have become common. Greenwashing, where companies falsely label plastics as “biodegradable,” can mislead consumers and lead to improper disposal.

To combat this, standardized tests are necessary to assess actual biodegradability under specific conditions. These tests determine whether a plastic truly breaks down into harmless components within a given timeframe.

Different regions have developed certification standards to define whether a plastic qualifies as biodegradable or compostable.

These standards set specific criteria for how quickly and under what conditions a material must degrade.

- ASTM D6400 (U.S.) – Establishes compostability requirements for plastics in industrial composting facilities, ensuring complete breakdown without toxic residues.

- EN 13432 (Europe) – Defines the conditions under which packaging materials must degrade, requiring at least 90% disintegration within 12 weeks.

- ISO 17088 (Global) – Provides general international guidelines for compostable plastics, aligning with national standards.

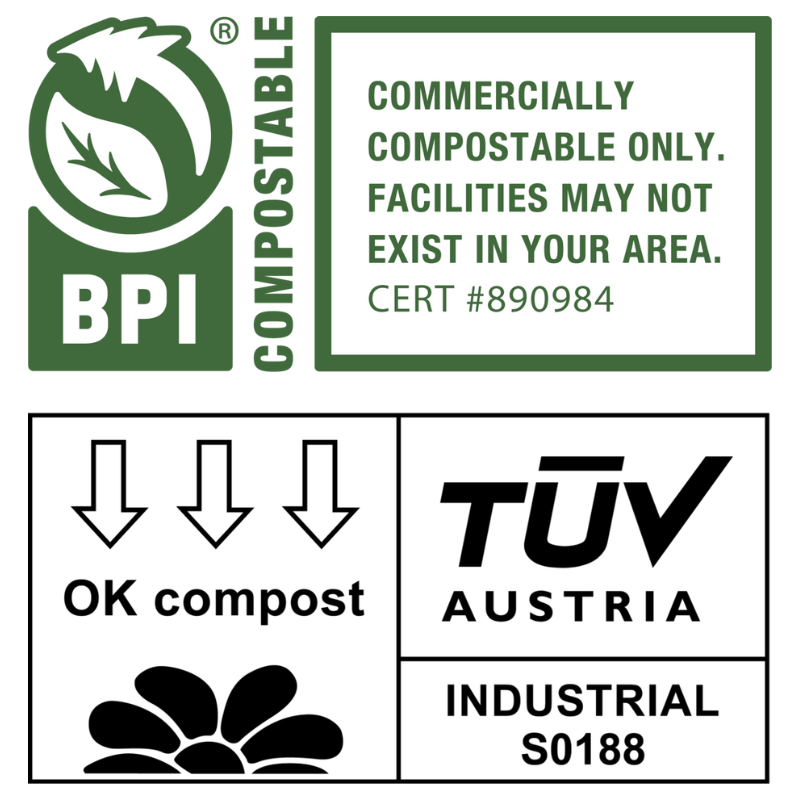

Certification Bodies

Various organizations certify biodegradable plastics to help consumers identify legitimate compostable materials. Some of the most recognized certifications include:

BPI (Biodegradable Products Institute) – North America

- Ensures compliance with ASTM D6400 for industrial compostability.

- Commonly seen on food packaging, cutlery, and compostable bags.

OK Compost (TÜV Austria)

- Certifies products that comply with EN 13432.

- OK Compost INDUSTRIAL indicates compostability in industrial settings, while OK Compost HOME certifies materials suitable for home composting.

Seedling Logo (European Bioplastics Association)

- Used across European markets to confirm compliance with composting standards.

Why Can’t I Use Compostable Plastics In Home Composting?

Industrial composting facilities are designed for rapid decomposition. They maintain temperatures above 50–60°C, creating the perfect environment for breaking down biodegradable plastics. High heat speeds up microbial activity, allowing materials like polylactic acid (PLA) to degrade within a few months.

Home composting, on the other hand, is far less predictable.

Most backyard compost piles don’t sustain high enough temperatures for long periods, especially in cooler climates. Without this heat, compostable plastics can take years to break down—or not decompose at all.

Another key factor is oxygen availability.

Industrial composting ensures consistent airflow, promoting aerobic decomposition. Home compost piles often suffer from uneven oxygen levels, leading to slower breakdown and, in some cases, plastic fragments persisting in the soil.

Even the composition of biodegradable plastics plays a role. Many require specific microbes to trigger degradation—microbes that aren’t always present in backyard compost bins. This means that instead of turning into nutrient-rich compost, these plastics might just sit there, breaking apart into smaller pieces without fully disappearing.

If you’re composting at home, stick to organic materials like food scraps, leaves, and paper products.

What Are Some Limitations of Biodegradable Plastic?

Biodegradable plastics sound like a dream solution to plastic waste, but are they really? While they break down faster than conventional plastics, they come with their own set of challenges. From durability issues to confusion over disposal, biodegradable plastics aren’t as simple as they seem.

1. Performance and Mechanical Properties

Ever left a compostable cup in a hot car, only to find it warped or melted? That’s one of the biggest issues with biodegradable plastics—many just don’t hold up like traditional plastics.

PLA (polylactic acid), one of the most common biodegradable plastics, is brittle and heat-sensitive, making it a poor choice for products exposed to high temperatures. For industries that rely on tough, long-lasting plastics—like construction or automotive—biodegradable options just don’t cut it.

2. Cost and Availability

Would you pay twice as much for a biodegradable plastic bag? Right now, many businesses don’t have a choice.

Because biodegradable plastics are still produced on a smaller scale, they remain more expensive than traditional petroleum-based plastics. Manufacturing infrastructure isn’t as developed, and in some regions, these plastics are hard to find. Until production scales up, cost will continue to be a major barrier.

3. End-of-Life Confusion

If a plastic bag says “biodegradable,” can you just toss it in your backyard compost? Not exactly.

Many biodegradable plastics require industrial composting—where temperatures soar above 50–60°C—to fully break down. The problem? Most consumers don’t have access to these facilities. This leads to improper disposal, with biodegradable plastics ending up in landfills, where they may take years to degrade.

Worse yet, when biodegradable plastics get mixed with regular recycling, they can contaminate the entire batch, making it harder to process conventional recyclables. So where do they really belong? That’s a question even experts struggle to answer.

4. Environmental Footprint

Think biodegradable plastics are completely eco-friendly? Think again.

Yes, they’re often made from renewable feedstocks like corn or sugarcane, but growing these crops takes land, water, and energy. Large-scale farming for plastic production could compete with food production, leading to deforestation and resource depletion.

And let’s not forget emissions—manufacturing biodegradable plastics still releases carbon dioxide, and if they break down in landfills without oxygen, they can produce methane, a greenhouse gas 30 times more potent than CO₂.

5. Fragmentation vs. True Biodegradation

Some biodegradable plastics don’t really biodegrade—they just fall apart.

Oxo-degradable plastics, for example, break into tiny microplastics when exposed to sunlight or oxygen. These fragments don’t disappear; they persist in soil, rivers, and oceans, harming marine life just like regular plastic.

If a biodegradable plastic doesn’t fully return to carbon dioxide, water, and biomass, is it really helping the planet? Or just delaying the pollution problem?

6. Potential Contamination in Recycling Streams

Plastics like polylactic acid (PLA) have a different chemical structure from polyethylene (PE) and PET, meaning they can’t be processed together. If mixed, they risk contaminating entire batches of recyclables, making it harder to produce quality recycled plastic. Most standard recycling facilities aren’t equipped to separate them properly.

Some advanced facilities can process PLA separately, breaking it down into lactic acid for reuse. However, these facilities are limited, and setting up specialized collection and processing systems is still a challenge.

Biodegradable plastics aren’t a magic fix for plastic pollution. They degrade faster than traditional plastics, but only under the right conditions.

Until better infrastructure, clearer disposal guidelines, and stronger material development are in place, they remain a partial solution at best.

The Future of Biodegradable Plastic

Biodegradable plastics hold promise, but their future depends on scientific advancements, policy changes, and better waste management. Researchers are working on improving mechanical properties, cost-effectiveness, and biodegradability speed, with innovations like genetically engineered microorganisms that break down plastics more efficiently.

For true impact, biodegradable plastics must fit within a circular economy—designed for reuse, composting, or specialized recycling rather than being a license for wasteful consumption. Governments are already pushing for bans on single-use petroleum-based plastics, accelerating the shift to compostable alternatives.

Scaling up industrial composting facilities and educating consumers on proper disposal are key steps toward making these materials viable. If managed correctly, biodegradable plastics could reduce marine pollution and environmental harm, but they are not a stand-alone solution.

The real goal? Reduce, reuse, and recycle first—then choose biodegradable where necessary. A sustainable future requires a balance of innovation, responsible consumption, and better waste management. Let’s make the right choices, not just for convenience, but for the planet.